In Brief

With payers expressing wider interest in value-based contracts (VBCs) and more manufacturers making these contracts a pillar of their competitive strategies, we revisit the state of VBCs in the U.S. Regulatory uncertainty, implications for government pricing and the complexity of tying rebates to patient-level outcomes continue to constrain the design of VBCs, but payers have too strong an incentive to "pay for performance" to decline pursuing VBCs, when feasible and their market power allows. As constraints release, the pace of deals could accelerate quickly, disadvantaging manufacturers who have not built the necessary capabilities. We outline actions manufacturers may take now to be competitive in the present environment and to prepare for future expansion in the number and ambition of deals.

What is Value-Based Contracting, and Why is it of Interest?

We consider value-based contracting (VBC) to be any scheme that accomplishes the following:

- Identifies a set of outcomes, mutually recognized by payers and manufacturers, that reflects the clinical or economic benefits provided by a therapy for a targeted use in a specified population.

- Defines the measurement of these outcomes in real-world populations and specifies the data sources, processes and thresholds that represent "good" and "poor" outcomes.

- Specifies the formula that determines the net price or reimbursement (contingent upon the measured outcomes) and its implementation (generally as a rebate). This implementation should be feasible given constraints of data privacy and availability, and the contract terms should include auditing and adjudication acceptable to both parties.

In a 2016 survey of payers (EMD Serono Specialty Digest), 15 percent of payers said they had a value-based contract in place and another 30 percent planned to implement one in the next year. Biogen has cited VBCs as a key tactic to support their muscular sclerosis franchise in the face of new competition. Amgen has enlisted VBCs to protect EnbrelTM from pending biosimilars.

Eli Lilly and Anthem have published a joint call to address regulatory uncertainty and promote wider adoption. To understand this wide and growing interest, consider the pain points in the traditional contracting practiced today:

- Prices are unit-based, but incremental value and unit consumption differ across indications, populations and individual patients.

- Credits for offsetting costs are limited to the benefits payers manage and to the risks they own.

- High turnover in covered lives limits the horizon for crediting value to about three years. This strongly disadvantages therapies that improve long-term disease progression, or cellular and genetic therapies that deliver a lifetime of benefits but are front-loaded in cost to the payer.

- Only clinical trial data and health economics outcomes research (HEOR) models inform initial pricing and access, with no clear avenue to consider real-world effectiveness (RWE), nor to incent the collection of RWE data after launch.

Aside from other forms of innovative pricing (e.g., capitation, installment payments, indication-specific pricing), value-based contracting may address these pain points, particularly those associated with measuring and rewarding value in real-world clinical practice. By construction, VBCs shift the risk of translating trial data to real-world effectiveness onto manufacturers. Whether manufacturers are better positioned to accept this risk is questionable, but it helps payers make their expenses more predictable - a competitive advantage when quoting premiums to individuals and enrolling employers. It also supports payers' marketing that they are innovative in "paying for performance" and bending the cost curve."

Express Scripts' SafeGuardRxTM program illustrates this comprehensive approach. In therapeutic areas with significant budget impact (e.g., oncology, immunology, cholesterol, hepatitis C virus, diabetes), Express Scripts offers a suite of disease management programs, provides customers inflation protection, heightens manufacturer competition via indication-level formularies and uses VBCs to avoid reimbursing for use in patients who do not respond to therapy.

While manufacturers are on the "losing end" of this risk acceptance, in competitive therapeutic areas where payers are willing to close their formularies, participation in VBCs can be the price of entry. Manufacturers may use VBCs to counter payers' objections about the validity of trial data. In the longer term, through VBCs, manufacturers signal their commitment to cost-effective innovation, and without a more predictable link between value and pricing, they face further declines in ROI as funding tightens.

The Reality of Value-Based Contracting (so far)

While interest in VBCs is widespread, the number and ambition of deals executed have been limited by:

- Compliance concerns regarding the federal Anti-Kickback Statute

- Spillover of rebates to government pricing

- Availability and privacy of needed data and the complexity to collect and analyze it

- Concern over implied off-label use or marketing

The federal Anti-Kickback Statute broadly prohibits remuneration to induce or reward services paid by government programs. When a manufacturer assumes the risk of real-world outcomes to obtain formulary coverage, there is a risk it could be interpreted as such remuneration without an explicit Safe Harbor provision that is yet lacking. Fees paid by manufacturers to administer VBCs could be deemed "bona fide service fees" under a fair market value (FMV) assessment, but it is challenging to extend this approach to rebates that are determined and paid only after formulary coverage is provided.

Medicaid 340(b) pricing is tied to the lower of a minimum discount from AMP (generally 23.1percent%) or the manufacturer's "best price" ever quoted to customer. Existing exclusions for "free goods" do not translate to VBCs. When a VBC states that a manufacturer is not paid for patients who do not respond to therapy, such a transaction would be valued at zero dollars. While averaging mutes the AMP/average sales price (ASP) impact, a single VBC could reset best price, placing an effective limit on the magnitude of rebate offered. As VBC rebates are determined over long time periods, a methodology is required to estimate and then "true up" rebates on a quarterly unit-basis. Design should reflect these constraints, e.g., by tying rebates to aggregate outcomes with caps on the maximum rebate offered in each quarter. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in reiterated in July 2016 that existing guidance on best price should hold for VBCs, so that this barrier persists - even if CMS in the same release encourage manufacturers to enter VBCs with state Medicaid agencies.

Compared to a traditional contract, the design and execution of VBCs can be far more complex, depending on the outcomes employed. Simplest are measures such as adherence, regimen add-on/switches or use of rescue medication therapy, that are covered under the pharmacy benefit and can be benchmarked against third-party data. When outcomes refer to medical expenses, resource utilization or laboratory readings, VBCs are complicated by the split management of pharmacy and medical benefits, uneven ownership of medical risk and data availability. Collection and analysis of these data and the auditing and adjudication of contracts are expensive and are constrained by HIPAA rules on use of personalized data. Where the outcomes are not directly tied to the indicated label, there may be additional concerns over interpretation as off-label communications.

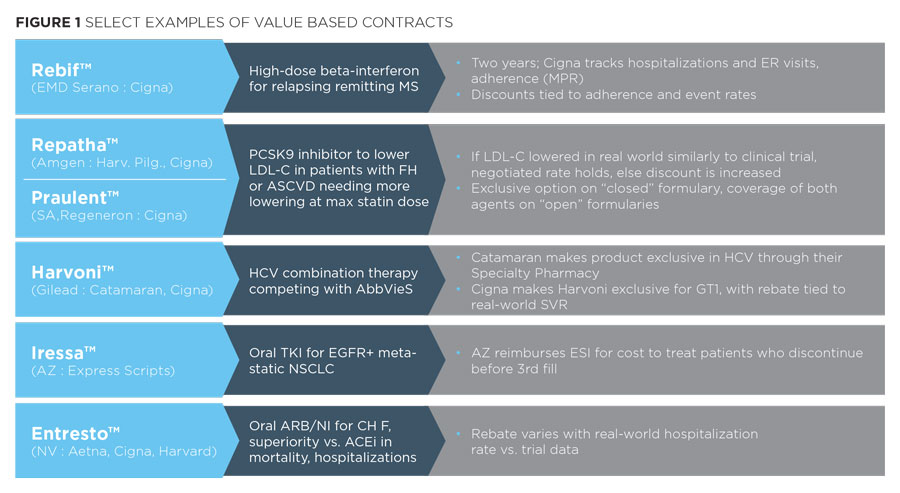

Reflection these constraints, recent VBCs have been relatively modest in design (see below).

We see among these examples a few common attributes:

- The drugs involved often face significant competitive pressure for formulary position, in therapeutic areas with major budget impact - e.g., the PCSK9 inhibitors, HCV therapies

- The outcomes measures rely upon compliance or upon a readily measured outcome that is directly tied to the drugs' efficacy in the use for which it is intended in the label

- Payers privately and publicly questioned the validity or clinical significance of trial outcomes

When exploring potential VBCs with payers, their responses are consistent with Figure 1.

- There is little appetite for "exploratory" outcomes to reward clinical benefits not already demonstrated in the pivotal trials. Rather the focus is to off-load the risk that the drug, when used in a real-world population, does not deliver outcomes that live up to the trials' promise.

- Payers show little interest in supporting premium drug pricing by considering offsetting savings in medical expenses, citing uneven exposure to the medical risk and necessary data.

- Payers hesitate to enter value-based contracts longer than three years, as would be necessary to establish long-term outcomes benefits.

- If a drug class does not significantly impact their budget, payers view the expense and complexity to execute a value-based contract as not warranted.

Case example: Novartis' EntrestoTM

EntrestoTM, a combination ARB plus a novel neprilysin inhibitor to treat chronic heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction, showed such superiority over the ACEi enalapril that the pivotal PARADIGMHF trial was halted early (approximately 5 percent ARR in composite CVdeath + HF hospitalization and approximately three percent ARR in all cause mortality). Access wins were slow to come, in part due to a July launch falling at an unfortunate time in the Medicare D cycle. But payers could also raise questions: How much benefit is due to the ARB (Gx valsartan)? Is 10 mg an appropriate enalapril dose for SOC?, Would you see such fewer hospitalizations without the continuity of care in a trial? Novartis entered VBCs with Aetna, Cigna and Harvard Pilgrim tying rebates to the observed frequency of HF hospitalizations. "Competitive drug prices are important, but equally so is ensuring that customers' medications are actually working as well as, or better than, expected," said Christopher Bradbury, Cigna's senior vice president in a press release announcing the deal granting EntrestoTM preferred-brand status subject to prior authorization on commercial plans. "Outcomes-based contracts require that prescription medicines perform in the real world at least as well as they did during clinical trials and are a valuable tool for improving health and managing costs. When pharmaceutical companies stand behind the performance of their drugs through these kinds of contracts, we can deliver the most value to Cigna's customers and clients for the money they are spending."

Guidance for Manufacturers

Faced with this current state of VBCs, manufacturers are debating their level of engagement and investment. In the near-term, VBCs tying rebates to adherence or real-world efficacy measures (e.g., LDL-C, HbA1c, hospital admissions) are becoming the cost of entry to gain positions on closed formularies, at least in major competitive therapeutic areas. To participate, manufacturers must gain comfort in assuming real-world effectiveness risk, understand the full economics of deals including spillover to government pricing and ensure analytics and compliance processes support VBC execution.

When the government eventually addresses the "best price" and Anti-Kickback Statute barriers - and with rising price pressure it is hard to believe it never will - the depth of value-driven rebates and the pace of execution will grow. While deals will likely remain focused on "warranties" of real-world effectiveness in labeled indications, manufacturers that can paint more comprehensive and compelling pictures of real-world effectiveness will gain the edge in formulary competitions. To be positioned to offer such data through trial end points and a real-world evidence strategy piloted in trials and maintained in post-marketing use requires foresight and planning when setting development strategy. With such long lead times, manufacturers cannot afford to wait and respond to VBC opportunities on a brand-by-brand basis. Rather they should launch a concerted, cross-functional, cross-brand effort to:

- Articulate prototypical designs and identify compliance and operational challenges (now and future) and the means to mitigate them, and develop valuation and risk-assessment methodologies

- Obtain consensus on when to pursue these VBC types and the policies/limits to enter them

- Map current and pipeline assets against these criteria to prioritize leads for execution

- Develop the analytical, IT, medical and commercial capabilities to execute prioritized deals - leveraging a common base of expertise and resources across the company for scale and quality

- Build account management skills and payer relationships to communicate and negotiate VBCs

- Incorporate VBCs into commercialization decisions, early in development, as part of standard processes for asset development check-points and portfolio strategy reviews

The very complexity that makes VBCs daunting also dictates a lengthy period to develop and refine the approach. While it may be tempting to let competitors invest to lead the way, it will be slow for laggards to catch up, and if this deferral cedes a "1 of 1" formulary position, the price of delay is dear.